At a Glance

- The infrastructure that determines how money travels from start (donor) to finish (researchers), is complex and unoptimized.

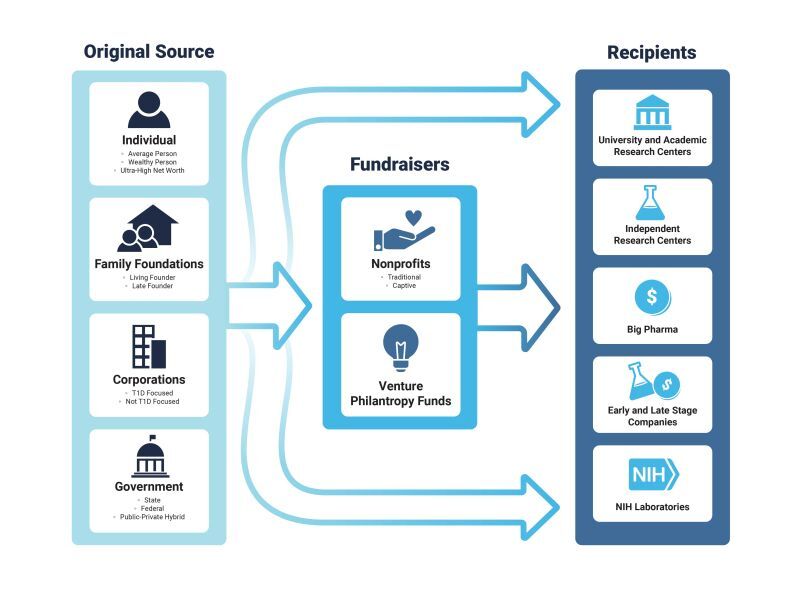

- The labyrinth of this structure is broken down into 3 pillars: Original Source, Fundraisers, and Recipients.

- Unspecified donations, conflicting priorities, and a lack of defined ‘high potential projects’ and a way to measure their success, inhibit cure progress by diluting resources.

- If changes are made to direct the flow of funding with measurable objectives and accountability, it would expedite cure progress.

August 22, 2024

Money is the lifeblood of research. Yes, this is obvious, but it is also essential to consider. With money, labs are funded, key equipment is purchased, talented scientists are paid, and startups get off the ground. With more money, more can be done, assuming most of it is used wisely.

For many researchers, both academic and commercial, the pursuit of money to fund projects is a necessary part of the job. One key reason research progress is delayed is a lack of funding for the next phase of research. However, when money is available, research can move along quickly and without delay. None of us want promising research postponed for any reason. Those of us living with T1D want results now. Money makes this happen.

Where does the money for T1D research come from, and who decides how it will be used? This report answers that question at a macro level. On one hand, the answer to this question is a complex ecosystem with millions of moving parts. On the other hand, at a higher level, it is quite straightforward. The infographic below summarizes the macro money flow, from the various sources to its variety of recipients. The remainder of this report will elaborate on this infographic in more detail. We will include related dollar figures when possible, but for many entities, the data is simply not available.

Original Sources

There are four main sources of funding for T1D research:

1. Individuals

One of the largest and continuous sources of money for T1D research comes directly from regular people like you and me. We give through direct donations, by supporting our friends and family, and by participating in walks, rides, and galas.

Often, we give to a big nonprofit organization, like Breakthrough T1D and others, who we trust with spending our money wisely and in line with our priorities. Other times we give directly to research universities and medical centers that provide front-line care. All of this giving is a good thing and reflects the best of our human instinct for generosity.

Along with this giving comes responsibility. The organizations to whom we give have the responsibility to use it in the spirit with which it is given. If we want to fund cure research, those who receive the money should use it to fund cure research. Sometimes this is true, but more often, as our regular readers know, it is not the case. The donor also carries responsibility when giving—to contribute to organizations that fulfill their objectives and, in the case of larger gifts, to follow up and ask how the money was used.

A donor may give to a nonprofit, attracted by prominent cure messaging, but the institution can allocate those dollars elsewhere if the purpose of the donation is not explicitly stated. Additionally, there are no pre-determined objectives that demand a certain percentage of raised dollars go to specific research, greatly limiting the drive to raise funds for cure research.

2. Private Foundations and Trusts

A second major source of funding for T1D research comes from private foundations and trusts. Typically, these organizations are set up by wealthy families to manage their philanthropic activities. Many have founders who remain active in management and decision-making; others are organizations whose founders have passed, operating with a professional management team led by a board of trustees (composed typically of next-generation family members and trusted advisors).

Most are set up to operate with perpetuity, giving an annual amount that is less than what the foundation earns in interest and investment returns from its principle. Others are set up to spend all their money within a set time frame, most famously articulated by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. In general, private foundations and trusts do not raise money from the public (some accept donations).

While thousands of these foundations give to T1D research each year, only the largest are well known and are very powerful. With comparatively few decision-makers, they can make large, transformative gifts quickly. The most well-known example of a major private foundation supporting T1D is the Helmsley Charitable Trust, donating between $50-$250 million to T1D for almost a decade.

In general, the T1D community is fortunate to have these private foundations and trusts. These entities could choose to give to any cause their leadership prioritizes, and we deeply appreciate when they choose T1D.

3. Corporations

The third major contributors to T1D research are commercial entities. There are several different ways companies fund T1D research. The most common path is through its own internal research programs. Big pharma invests a large portion of its annual income in research. Smaller entrepreneurial companies who have little or no annual income raise money from investors who hope to cash in if the product is a success. The available data is not sufficient to ascertain how much money is allocated to T1D research each year by commercial entities, but presumably, it is substantial.

The second path commercial enterprises utilize to fund cure research is by funding or investing in other companies. Big pharma often invests strategically in a range of promising new technology companies to supplement their own internal research programs. This approach is a win-win: The start-up gains the expertise of the larger company while the latter gains the option of a deeper partnership as the technology is proven, or, the option of acquisition, which occurred between Provention Bio and Sanofi in 2023.

The third path is making gifts and grants to big nonprofit or academic centers. Notably, many of the largest donors to the American Diabetes Association are big companies. Regrettably, very little of that money reaches T1D research.

4. Governmental Bodies

The most complex contributors to T1D research are government agencies. Generally, the money these organizations allocate comes from federal and state taxes. Sometimes, it comes from a dedicated bond issuance backed by taxpayer dollars. The three major vehicles of government funding are:

- Federal Programs. The US federal government funds the FDA, a vital component of research development that ensures efficacy and safety, and the NIH, one of the largest funders of medical research grants throughout the US. Last year, the NIH spent about $202 million on T1D research—$142 million from the Special Diabetes Fund and the rest from the general diabetes research budget.

- State and Municipal Grants. These grants are gathered from state agencies and taxpayer dollars to fund research that local governments believe will spark economic activity. Some states use these vehicles actively to incentivize the development of medical research, most notably California, New York, and Massachusetts.

- Public/Private Hybrid Authorities. These entities are independent organizations with a specific purpose funded through a dedicated bond issuance backed by state or municipal guarantees—essentially committing taxpayer dollars to backstop the bond payments. One of the most notable examples is the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM), established to spark the development of a regenerative medicine industry in California. CIRM’s initial funding came from a bond issuance that was voted on by California residents. CIRM was an early funder of ViaCyte, ultimately committing about $43 million to the company.

Fundraisers

Fundraisers are nonprofit entities that raise money from the public and distribute it to researchers. These are legally and operationally independent entities. Guided by a mission and purpose, their scope of giving may be varied and broad or narrow and focused.

These entities might be described as ‘middlemen,’ but this term short-shrifts the amount of influence and power they have on shaping a broader research agenda. As an example, Breakthrough T1D, which maintains deep relationships with principal investigators and government officials throughout the world, is uniquely positioned to shape the agenda.

The most common structure of the fundraiser is nonprofits which raise money and make grants. Most are smaller organizations that raise money in their local communities. Breakthrough T1D and the American Diabetes Association are the two largest diabetes nonprofits. Last year, Breakthrough T1D raised $224 million and gave $98 million to research grants; The ADA raised $145 million and gave about $22 million to research grants.

A few are ‘captive’ nonprofits with the purpose of raising money for one particular research center. The most notable examples of captive T1D nonprofits are the DRIF which raises money for the Diabetes Research Institute (DRI) at the University of Miami (raising about $7 million last year), and the Children’s Diabetes Foundation which raises money exclusively for the Barbara Davis Center for Diabetes (raising about $4 million last year, almost all through a mega-gala that has become a marquee social event in Hollywood).

Lastly, a recent entrant to this middle tier is venture philanthropy funds, which raise charitable dollars that are invested rather than given out as grants. A venture philanthropy fund is a registered 501(c)(3), mission-driven, and committed to spending its money by investing in companies that might fulfill that vision. These funds typically buy stock in the company in an early investment round and receive a share of the profits from either annual operations or its sale that, if successful, can be a substantial return. The most well-known T1D venture philanthropy fund is the T1D Fund, an independent subsidiary of Breakthrough T1D. The fund has $70 million in assets and has invested in thirty-one companies since its inception in 2016.

Recipients

Recipients are the final destination. These are the research centers, scientists, and principal investigators who deploy the money for their research. There are five primary types of recipients:

1. Universities and Academic Research Centers

University-based research laboratories working on diabetes are operating throughout the world. In general, higher GDP economies support a disproportionate amount of academic research facilities. Almost every state in the US has a major university research center and many states have multiple. Some of these universities have a dedicated diabetes center, such as the Naomi Berrie Diabetes Center at Columbia, DRI at the University of Miami, and the Joslin Diabetes Center affiliated with Harvard.

2. Independent Research Centers

Many nonprofit research centers are not part of or directly affiliated with a specific university. These may be connected to major regional hospital centers or operate independently. Notable examples conducting T1D research include Scripps Research, City of Hope, and Benaroya Research Institute, among others.

3. Big Pharma

The big, well-known pharmaceutical companies and medical device companies conduct a large volume of T1D research and are instrumental in scaling up, manufacturing, training physicians, and bringing a product to market. A few examples active in T1D research include Eli Lilly, Medtronic, and Sanofi.

4. Early and Late-Stage Development Companies

There are hundreds of small and mid-sized research companies conducting T1D research. A few of the most notable in recent years are Provention Bio, acquired by Sanofi for $3 billion, and Vertex Pharmaceuticals, testing a stem cell-derived beta cell line in human trials.

5. NIH Laboratories

NIH, funded by the federal government, conducts its own research, some of which is focused on T1D.

Optimizing for a Cure: Who Should Do What?

With so many different entities funding and conducting research, the ecosystem at times resembles a playground free-for-all. Who does basic research? Animal testing? Human trials? Manufacturing and scale up? Does everyone try to do everything?

The answer is yes and no. Academics want to get published, secure lab funding, and make tenure. Small and medium-sized companies want to build a blockbuster product that leads to great wealth. Big pharma wants to keep growing to drive up their stock price. In this sense, everyone wants to retain as much IP as possible. It is messy.

However, there are some natural divisions of strength and advantage that, if followed, we believe would unlock substantial efficiency and effectiveness. In general, universities are best at conducting exploratory and early-stage research. The absence of commercial pressure for sales and profit allows researchers to explore basic research whose practical application may be unclear. Since traditional investment money is less likely to support these activities, government grants are essential, and the NIH is an essential funder for this early research.

On the other extreme, big pharma has a real advantage in later-stage research, proven by animal and early human trials. Its large bank accounts can help a promising technology get through the very expensive final stages of human trials. Big pharma is also uniquely capable of figuring out how to set up manufacturing, distribution, health care provider education, and marketing.

The middle ground—between exploratory and later stages—is where the big nonprofits play a critical role. Many projects struggle to move from solid results in animal testing to human trials, which requires a heftier budget, deep regulatory knowledge, and a professional infrastructure. It is too early for big pharma but too intensive for academic laboratories. Many projects get stuck. Nonprofits, however, can play a unique role in providing the bridge to human trials in terms of both funding and expertise.

We believe that if this structure is adhered to more closely, much more would be accomplished.

Impact

Ultimately, money is the catalyst that pushes breakthroughs in T1D research. Without someone to foot the bill and proclaim exactly where they want their money to go and what they want it to fund, dollars can be sent elsewhere on the whim of others who hold different priorities. Having the ability to influence where the money goes is the most important factor in fueling research.

Not all research projects are equal. It is imperative that projects with the greatest potential receive priority funding, with a consistent definition of what constitutes a ‘high potential project.’ The consequence of not doing so is to widely disperse dollars to studies with extreme differences in quality, diluting funding that could be used solely for projects with a high chance of becoming a Practical Cure in the near future. A timetable must also be enacted to demand accountability. Without set definitions, timetables, and motivating factors, there is no push to deliver a Practical Cure for T1D.

What can you do? Tell them how you want your money used, and insist that it is used to fund cure research.