At a Glance

- T1D has been documented for 3,500 years.

- In the Pre-Insulin Era, a T1D diagnosis was a death sentence.

- In the Post-Insulin Era (1922+), patients struggled to control glucose, and many still suffer dire complications.

- Major advances in T1D treatment (pumps, insulin, CGMs) occurred within the last 25 years.

- T1D remains a brutal daily burden and still causes premature death.

- We have seen the Pre-Insulin Era and Post-Insulin Era: Now is the time for the Era of the Practical Cure.

May 21, 2024

The long history of type 1 diabetes is a tale of two major time periods: Pre-Insulin and Post-Insulin. For the first 3,500 years of human history, T1D was a death sentence. Those diagnosed died within two years, at most. It was not until 102 years ago that insulin, the only life-saving therapy for T1D, was created. After injectable insulin, the focus shifted to living with the disease, managing glucose to avoid horrendous complications, and maximizing quality of life.

For many decades after insulin, glucose testing was technically imprecise and improved only in more recent decades. At first, the only way to measure glucose levels at home was with urine test strips, often error-ridden and limited in ability. Blood tests were only administered in hospitals and took days to process. Insulin was derived from animals and administered with needles that were used over and over again, regularly resharpened and boiled. Dire complications were common, and few with T1D lived into their 70s.

Over the past twenty years, the quality of life for diagnosed patients has risen dramatically, with breakthroughs in CGMs, insulins, and insulin pumps. Today, people with T1D are more likely to live long, full lives provided they have access to the latest technology and use it with discipline. The day-to-day and minute-by-minute burden is still there, however, and unrelenting vigilance is required to prevent life-threatening complications.

Even with the latest technology, there are still far too many premature deaths from battling complications. Across the globe, an estimated 175,000 individuals die each year due to lack of care and resulting complications, and the prevalence of T1D is rising. The solution is not found in better technology. The only real solution is a Practical Cure.

There was the Pre-Insulin Era, marked by certain death. Then there was the Post-Insulin Era, marked by glucose management. Now is the time to start the third and final era: the Era of the Practical Cure.

Pre-Insulin: The Era of Loss

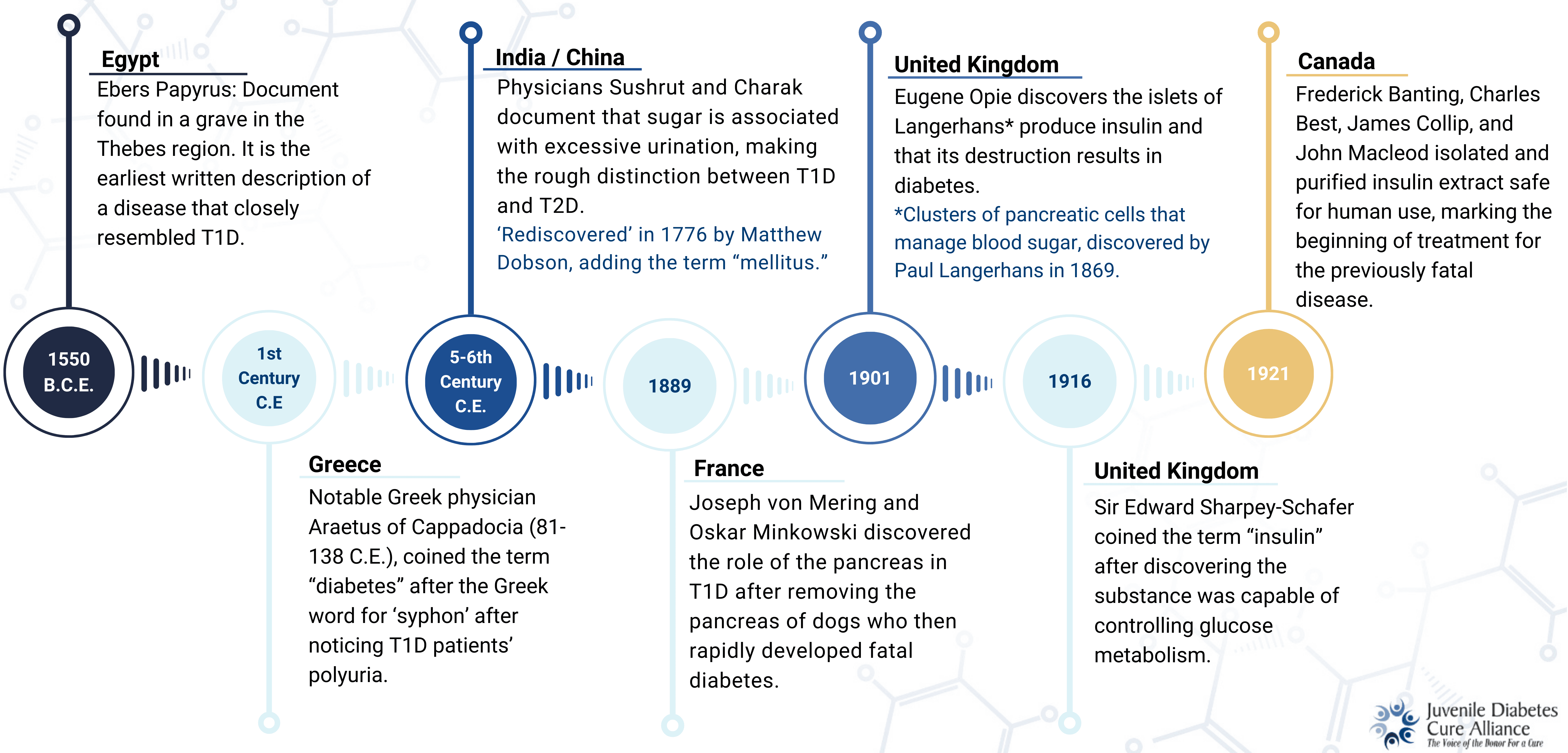

Figure 1. Timeline of Key Milestones: From Papyrus to Banting

T1D Has Been Known Since Antiquity

The first reference to T1D dates back to ancient Egypt, found in a fragile scroll known today as the Eber’s Papyrus. Georg Ebers, a respected Egyptologist, acquired the document from a vendor in Thebes, Egypt, who was said to have found it “between the legs of a mummy.” The Ebers Papyrus dates back to 1550 B.C.E., detailing a disease with clinical features identical to T1D. This is the first written document referencing T1D.

By 500-600 C.E., Indian physicians Sushrut and Charak made the first rough distinction between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. This was base-level, documenting T1D as present in the young, showing excessive “sweet-tasting” urination and weight loss; T2D was categorized as adult-onset, occurring in the wealthy who were often overweight.

As the science of chemistry developed in the 1700s, the scientific approach we are familiar with today began applying to the study of T1D. As a result, an increasingly in-depth understanding of the disease sparked many discoveries in a relatively short period (less than 150 years). Significant progress was made in understanding keystone characteristics of the disease, including the discovery of the Islets of Langerhans in 1869 and that ‘insulin’ controlled glucose metabolism in 1916.

These findings led to an invigoration of research seeking to treat the incurable disease. Surgeons and physicians around the world made significant strides studying insulin extract, dried pancreatic substances, and regularly performing pancreatomies on dogs to simulate type 1 diabetes.

At this point in time, the main obstacle to creating a viable treatment for T1D was the ability to purify insulin extract derived from non-human sources. Initially sourced from animals, purification was required to ensure the substance was safe for human use and potent enough to be effective.

The Brutal Allen “Starvation” Diet

Prior to insulin injections, a wide range of treatments were attempted, from the truly ridiculous to the truly brutal, and with little effect at best. Hope and prayer nostrums like snake oils, opium, special herbs, and dietary changes (both fasting and overeating) persisted with claims of “infallibly curing” diabetes mellitus, all without success.

The most notorious treatment was the Allen Diet (1913-1922), created by Frederick Allen and Elliot Joslin, considered some of the most prominent diabetes specialists in America at the time. Aptly referred to as the ‘Starvation Diet,’ it restricted its patients—mostly children—to the absolute minimum carbohydrate intake needed to sustain life. The diet allowed T1D patients to increase their life expectancy after diagnosis to a maximum of six years, making it the most ‘effective’ treatment up to this point in time. However, patients sacrificed their quality of life, becoming emaciated, skeletal, and listless. Joslin saw patients in a miserable constitution of mind and body, writing, “The aspect of these children was truly dreadful. We literally starved child and adult with the faint hope that something new in treatment would appear.”

Post-Insulin: The Era of Complications

The Insulin Revolution

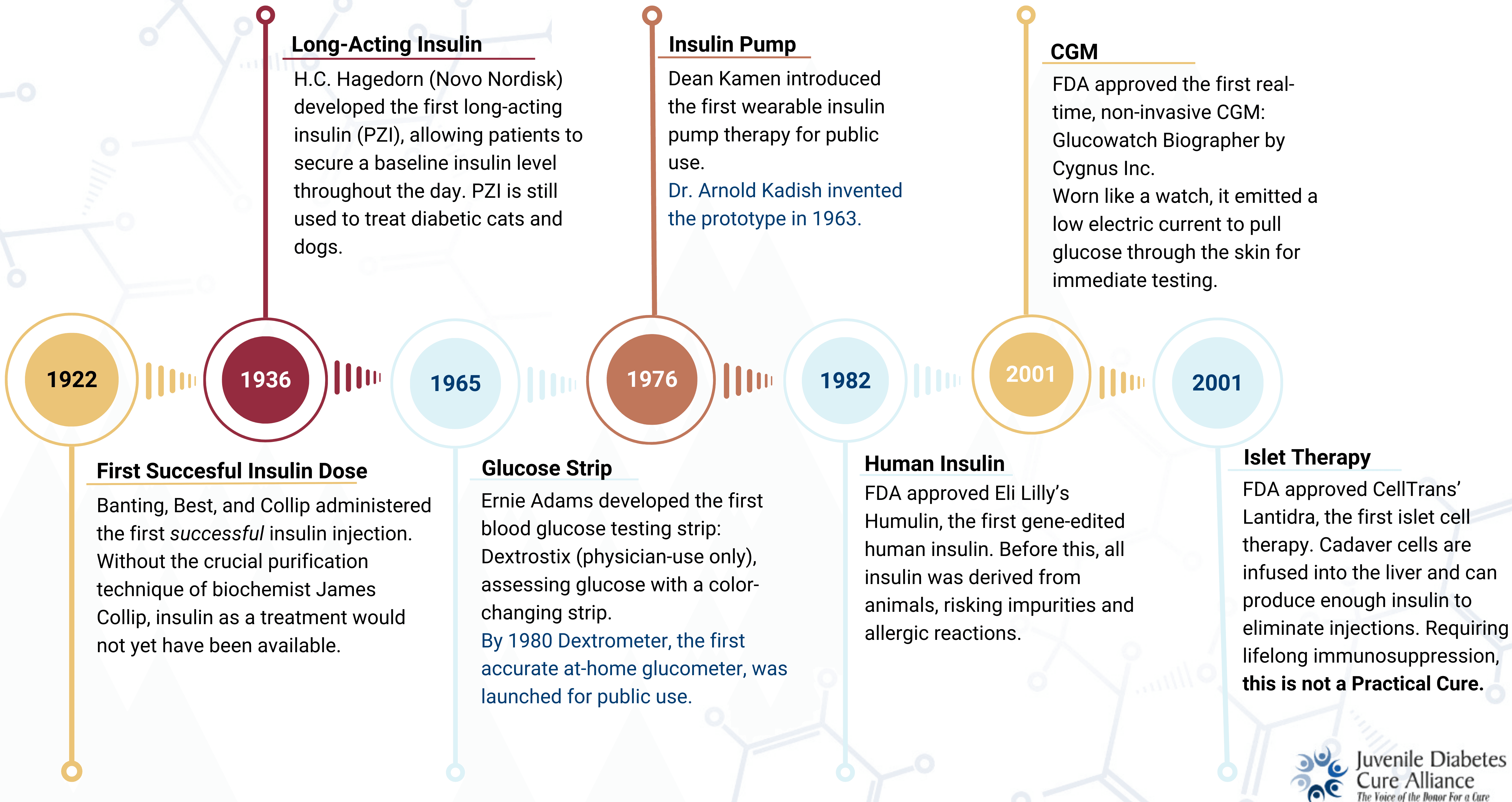

A fortunate collaboration between Sir Frederick Banting and Charles Best (utilizing the purification techniques of lesser-known biochemist James Collip) gave the world insulin in 1922. On January 23 of that year, the first successful dose of purified insulin extract was administered to Leonard Thompson, an emaciated fourteen-year-old boy of sixty-five pounds who was in active DKA. Leonard improved dramatically after the injection, and the success was hailed as a 'cure' for the previously fatal disease.

This discovery kickstarted a new era of diabetes research with arguably the best scientific advancement of the 20th century. Purified insulin meant a patient with T1D that would have survived anywhere from a few weeks to a few years without treatment, could now live.

Following the success of this first patient, Banting, Best, and Collip worked to purify their insulin further and to figure out how to produce it on a scale large enough to satisfy global demand. By 1923, the team partnered with Eli Lilly and was able to manufacture enough quality insulin to supply the entire world.

Fourteen years later, in 1936, the modern distinction between type 1 and type 2 diabetes as we know it today—T1D as insulin deficiency and T2D as insulin resistance—was established by Sir Harold Himsworth.

Figure 2. Timeline of Key Milestones: From Insulin to Islet Transplantation

The Era of Complications

In the decades after insulin, practitioners and patients alike were blindsided by the resulting long-term complications of type 1 diabetes. T1D patients were now living long enough to experience the long-term consequences of wide-ranging glucose levels. A miscalculation at mealtime, too high or too low a dosage, could lead to glucose levels on either end of the extreme.

The collective impact of these fluctuations over time results in terrible health issues, including vision loss, dementia, heart diseases, kidney diseases, and nerve damage. While T1D was no longer an immediate death sentence, for many, life was shortened due to battling complications.

As a result, there was a material shift in research focus toward improved glucose control and complications management that persists today.

Glucose Control Innovations: Insulin, CGMs, Insulin Pumps

It was not until the late 1970s/early 1980s that significant strides were made in improving glucose control. Innovations were introduced in both insulin quality and technology, offering profound and fundamental improvement in HbA1c and time in range. Faster and more effective long-lasting insulins were introduced, and continuous glucose monitors and pumps offered a more precise approach to glucose testing than pinpricks and test sticks. These interventions have greatly reduced complications and prolonged life expectancy after diagnosis.

Insulin Evolution

Since Banting and Best, there have been tremendous evolutions in insulin. The first insulins were derived from pigs and cows, were not as potent as the insulins of today, and were known to cause allergic reactions in some patients. Modifications improved purity and effectiveness. Later, analog insulins were developed and altered for fast-action or extended release.In 1982, the first genetically engineered, biosynthetic insulin identical in structure to human insulin, called Humulin, was sold. This new form of insulin was easier to source, more effective, and eliminated adverse allergic reactions.

Today, work continues to evolve insulin—faster action, stronger extended release, and smart insulin stored just under the skin to release in proportion to a rise in glucose levels.

Glucose Testing

Regular testing of glucose throughout the day is one of the key burdens of living with T1D, and it has come a long way since the early 20th century. The Benedict Test, introduced in 1908, was the first commercialized glucose test. It measured urine glucose using a copper reagent that turned color dependent on high or low sugar levels. Variations of urine testing remained the standard for glucose monitoring for over fifty years.In 1965 the first blood-glucose testing strip, Dextrostix, was developed. In 1980 the same company developed the Dextrometer, the world’s first accurate at-home glucose monitor, kickstarting self-monitoring as the standard of care. Early iterations of blood glucose testing devices had questionable accuracy and required larger amounts of blood, but improved quickly and are quite reliable today.

The latest innovation is the continuous glucose monitor (CGM). These devices have made remarkable progress over the past two decades and now provide highly accurate readings of blood sugar. They are connected directly to one’s body, usually on the upper arm, and provide data in real-time. Those who use these devices regularly see greatly improved time in range compared to regular meters and test strips. Today, CGMs are often used in tandem with insulin pumps.

Image Credit: Banting House National Historic Site

Insulin Pumps

The first insulin pump prototype was invented in 1963 by Dr. Arnold Kadish, delivering both glucagon and insulin for hospitalized patients while monitoring blood glucose automatically (see accompanying image). It was large and comparable to a backpack in both size and portability. Although laborious to carry, it marked the beginning of further streamlining diabetes care.The first commercial insulin pump for home use was Medtronic’s MiniMed 502, released in 1983. Insulin pump technology was quickly refined, with the ability to connect with CGMs and mobile devices, and with the ability to be worn instead as an ‘insulin patch’ adhered directly to the skin.

We’ve Come a Long Way, but There Is Still a Long Way to Go

While T1D is no longer an immediate death sentence, the global burden of the disease grows. An estimated 175,000 individuals die each year from T1D. For many in underprivileged countries where access to care is limited, T1D is still a life-ending diagnosis.

Advances in insulin and technology have made living with the disease easier, but complications still compromise quality of life, and early death is still very much a reality.

So, what does all this mean? Yes, the past 100 years have given us a wide variety of improvements in managing T1D. Refinements in insulin, pumps, and CGMS have greatly improved day-to-day and long-term health. But this is not enough, and a lifetime of struggling to treat the disease is unsustainable.

A cure is needed now as much as ever. This paper has reviewed the Pre-Insulin Era of Loss and the Post-Insulin Era of Complications.

Now, we propose the next era—the era of today—must be the Era of the Practical Cure.